Winter can be a challenging time for North American ungulates. As availability of food on summer ranges diminishes with accumulating snow, many ungulates in North America migrate to winter ranges to access available food. Although food is generally more available compared to summer ranges during this time, the nutritional quality of food on winter ranges is often marginal. To combat this seasonal limitation in nutritious food, many ungulates, including mule deer, rely on fat reserves to promote reproduction and survival. This well-adapted nutritional connection between deer and their landscape has allowed ungulate populations to persist for thousands of years, but what happens when a novel disturbance is introduced to winter ranges?

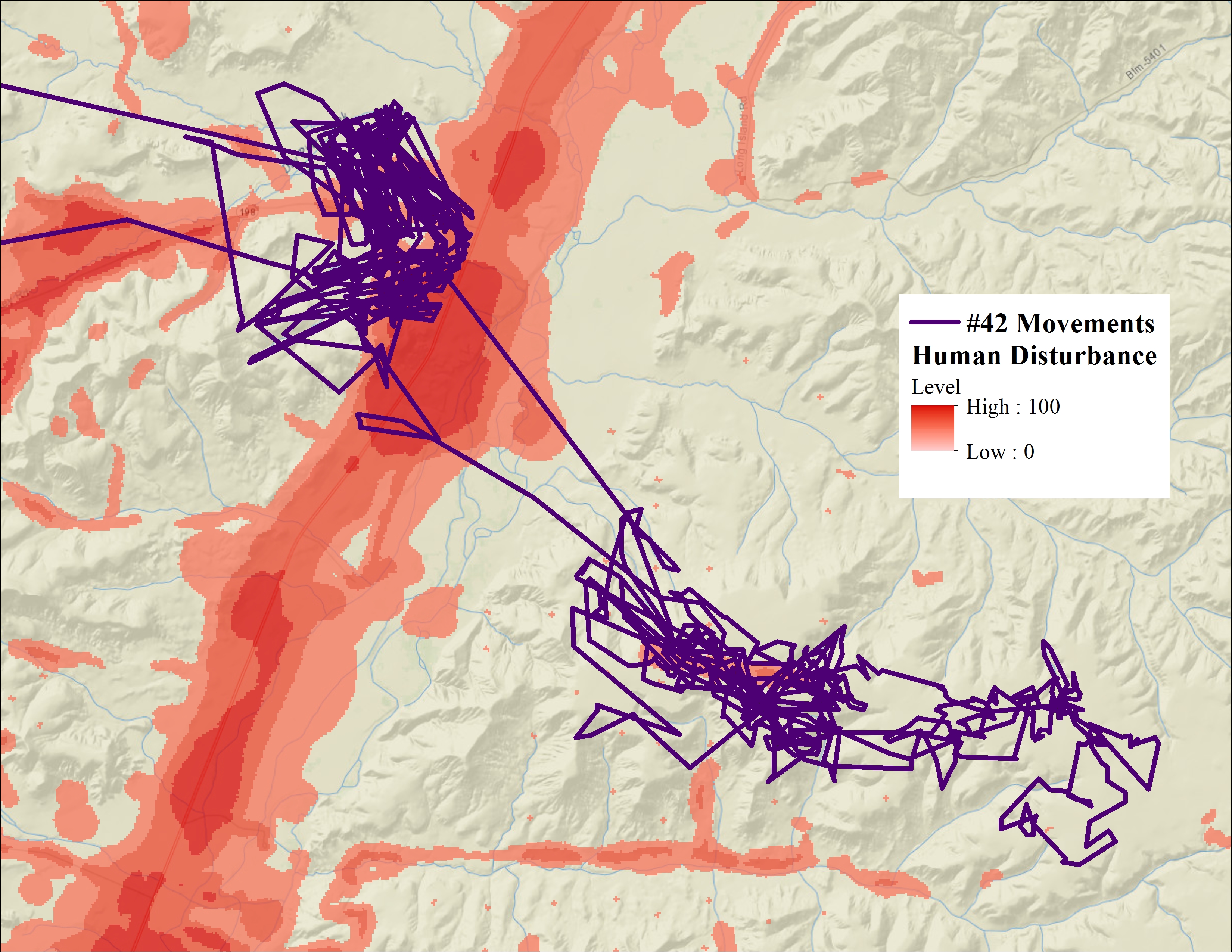

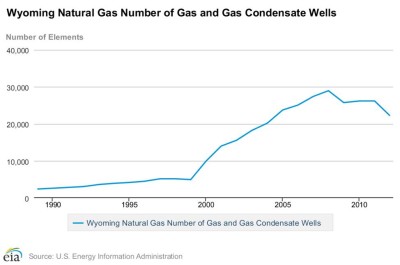

In the last couple decades, energy development has increased dramatically in many areas of western Wyoming, and much of which has occurred on sage-steppe winter ranges of many migratory ungulates including mule deer.  Coinciding with energy development have been noticeable declines in mule deer abundance; however, the cause for the observed declines are often speculative. We know from previous research that mule deer avoid energy development (by up to 7km), but the link between deer behavior and population trajectory is largely unknown. We hypothesized that behavioral responses that disrupt the nutritional relationship that deer have with their winter landscape may be one way human disturbance affects populations. More specifically, if human disturbance alters behavior of animals in a way that affects use of food, disturbance on winter ranges could reduce the carrying capacity (i.e., number of animals a range can support) of the landscape. Further, behaviors that alter the nutritional connection deer have with winter range may further affect populations because alterations to fat dynamics overwinter can have fitness consequences.

Coinciding with energy development have been noticeable declines in mule deer abundance; however, the cause for the observed declines are often speculative. We know from previous research that mule deer avoid energy development (by up to 7km), but the link between deer behavior and population trajectory is largely unknown. We hypothesized that behavioral responses that disrupt the nutritional relationship that deer have with their winter landscape may be one way human disturbance affects populations. More specifically, if human disturbance alters behavior of animals in a way that affects use of food, disturbance on winter ranges could reduce the carrying capacity (i.e., number of animals a range can support) of the landscape. Further, behaviors that alter the nutritional connection deer have with winter range may further affect populations because alterations to fat dynamics overwinter can have fitness consequences.

Our main objective was to evaluate how human disturbance on winter range affects the nutritional relationship between mule deer behavior and their landscape. Specifically, our research was aimed at addressing the following questions:

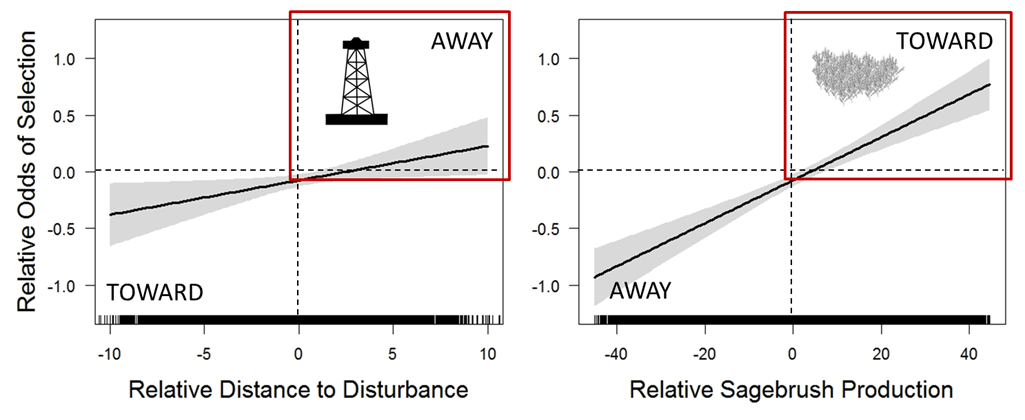

Do mule deer perceive human disturbance as a risk and exhibit behavioral responses of risk-aversion across multiple spatiotemporal scales?

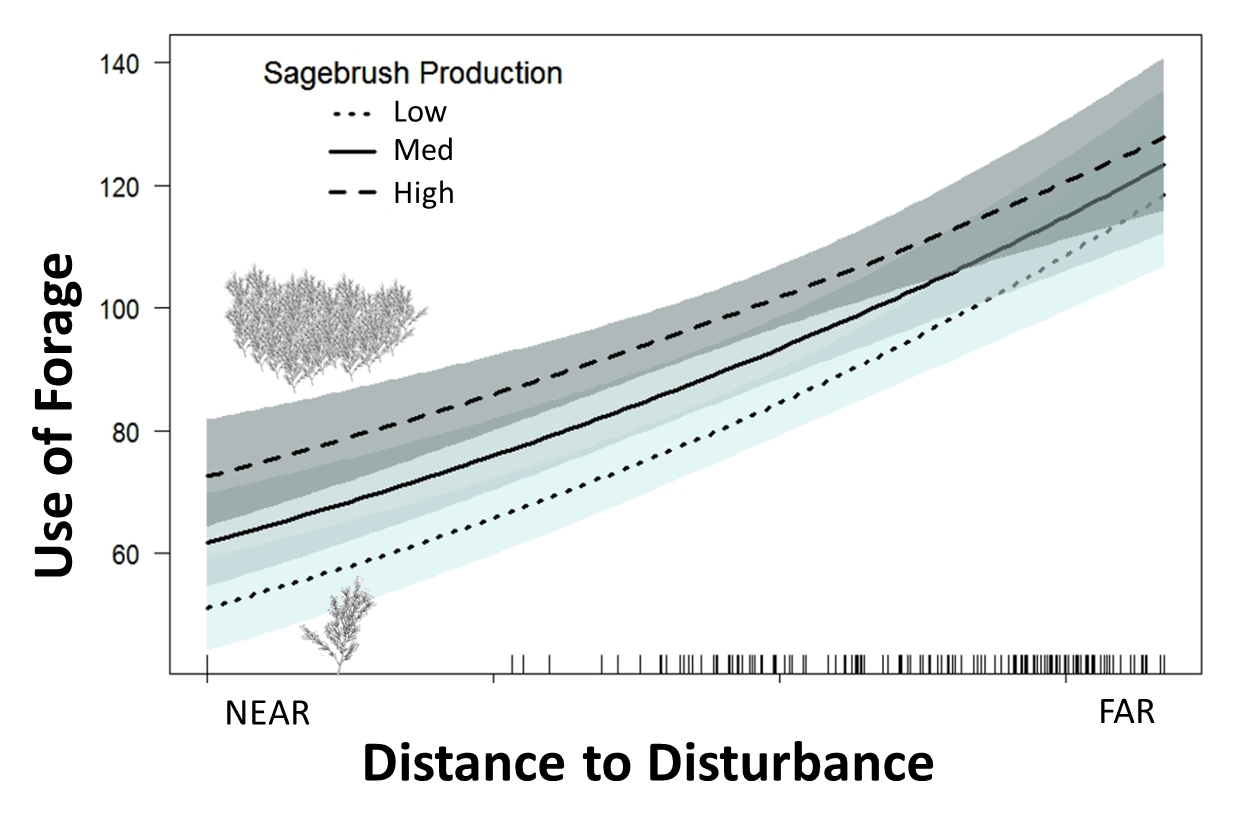

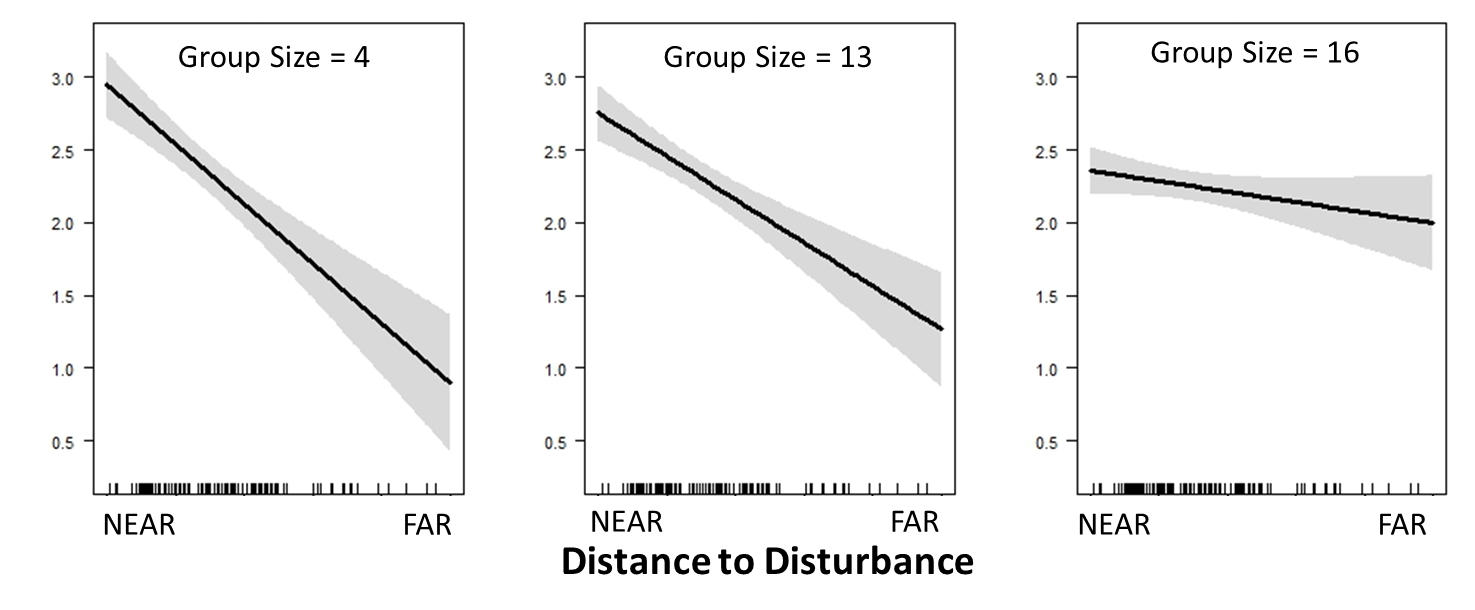

Do behavioral responses to human disturbance affect the way mule deer use available food on winter range?

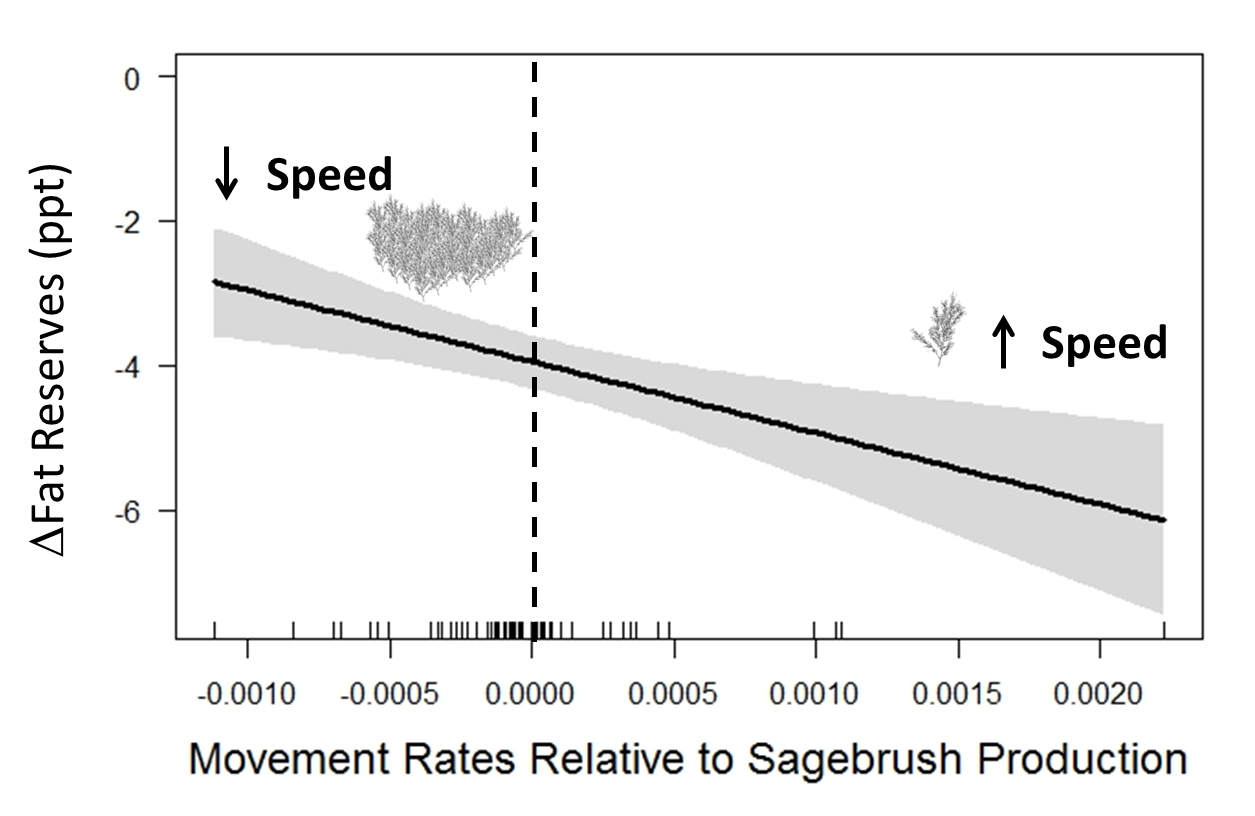

How do behavioral responses to human disturbance affect winter fat dynamics of mule deer?

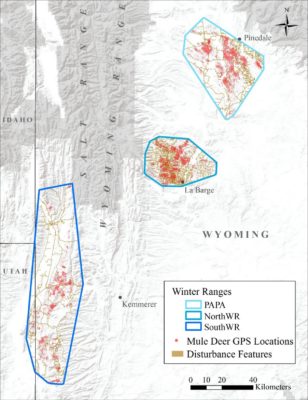

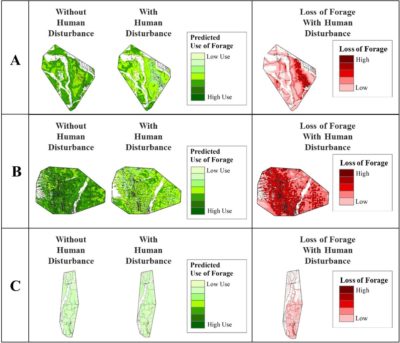

Between March 2013 and March 2015, we fit 146 mule deer with GPS collars among three winter ranges of varying degrees of energy development. Each fall and spring (as animals arrived to and departed from winter ranges), we recaptured collared individuals to measure nutritional condition (e.g., fat reserves) and life-history characteristics (e.g., reproductive status and age). Using GPS-collar data and direct observations, we evaluated behaviors in habitat selection, movements, and foraging in response to proximity to human disturbance. We then coupled behavioral responses and fat dynamics of mule deer with on-the-ground measurements of food quality and availability and exposure to human disturbance.

We found that mule deer, in response to human disturbance, exhibited risk-averse behavior across multiple scales which resulted in reduced use of available food near human disturbance. These pervasive behavioral responses to human disturbance prompted indirect habitat loss that was 4.6x that of direct habitat loss. Interestingly, we  observed little effect of human disturbance on fat dynamics overwinter; however, overall habitat loss that was amplified by indirect habitat loss from behavioral avoidance reduced the carrying capacity of winter range. Thus, revealing the pathway by which human disturbance affects population abundance.

observed little effect of human disturbance on fat dynamics overwinter; however, overall habitat loss that was amplified by indirect habitat loss from behavioral avoidance reduced the carrying capacity of winter range. Thus, revealing the pathway by which human disturbance affects population abundance.

As the global demand for energy resources remains, it is crucial that we understand the potential impacts that behavioral responses to energy development can have on populations of migratory ungulates. Thus, understanding how human disturbance affects the well-adapted nutritional relationship between an animal and its environment is pivotal for management of populations exposed to human disturbance. In quantifying the additional loss of food—and subsequent reduction in carrying capacity—resulting from behavioral avoidance of human disturbance, we can now provide managers and planners with a more accurate estimate of the overall habitat loss that can be anticipated in areas where energy development is proposed to occur.

Gallery

Contact

Samantha Dwinnell

Research Scientist

Haub School of Environment and Natural Resources

Bim Kendall House

804 E, Fremont St.

Laramie, WY 82072

Email: [email protected]

Kevin Monteith

Assistant Professor

Haub School of Environment and Natural Resources

Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit

Department of Zoology and Physiology

Bim Kendall House

804 E, Fremont St.

Laramie, WY 82072

Email: [email protected]

Hall Sawyer

Research Biologist

WEST, Inc.

200 S. 2nd St.

Laramie, WY 82070

Email: [email protected]

Gary Fralick

Wildlife Biologist

Wyoming Game and Fish Department

P.O. Box 1022

Thayne, WY 83127

Email: [email protected]

Project Lead

Sam is a Research Scientist at the Haub School of Environment and Natural Resources Her research is primarily focused on nutritional ecology of mule deer in western Wyoming.

Timeline

Data collected March 2013 – March 2015

Project completed 2017

Funding & Partners

Wyoming Game and Fish Department · Muley Fanatic Foundation of Wyoming · Bureau of Land Management · Wyoming Wildlife and Natural Resource Trust · Western Ecosystems Tech, Inc. · Boone and Crockett Club · Knobloch Family Foundation · Wyoming Governor’s Big Game License Coalition · Wyoming Outfitters and Guides Association · Wyoming Animal Damage Management Board · Bowhunters of Wyoming, Inc. · U.S. Forest Service · U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service – Cokeville Meadows National Wildlife Refuge