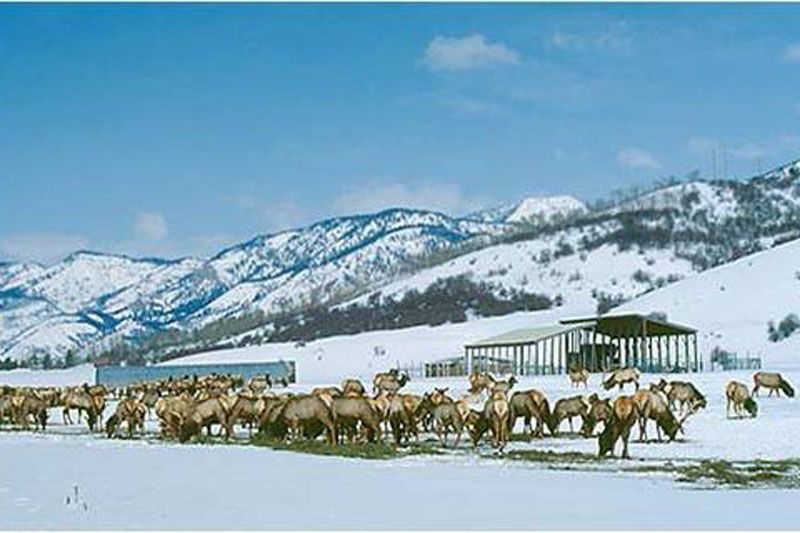

For many animal taxa, nutritional condition (i.e., fat levels) is a balance of food intake that increases condition versus energy outputs (i.e., cost of reproduction) that diminish condition. While nutritional condition gradients are common in nature, relatively little is known about how nutritional condition influences behavior. Current management practices in Wyoming offer a rare opportunity to evaluate the influence of nutritional condition on the behavioral strategies of a large, free-ranging population of elk (Cervus elaphus). The Wyoming Game and Fish Department (WGFD) operates 22 winter feedgrounds for population and disease management.

There are many native winter ranges nearby that also support elk, resulting in two groups that presumably differ in their nutritional condition. Our study views supplemental feeding as a landscape-scale experiment that manipulates the nutritional condition of elk. Feedground populations with consistent, reliable winter food supplies should show less inter-annual variability in body condition and come out of winter with higher body-fat levels than unfed elk. It is unknown whether fed elk make different cost-benefit tradeoffs or employ different strategies than unfed elk outside of winter owing to difference in winter fat losses.

The objectives of this study are to evaluate differences between fed and unfed elk in regards to 1) migration patterns, 2) summer habitat selection, 3) foraging, and 4) landscape-level distribution. In addition, parturition area delineation, interchange between fed and unfed elk, and brucellosis seroprevalence will be characterized. This work is being conducted collaboratively by investigators from our research group, WGFD, and the US Geological Survey, and will make use of existing fine-scale movement monitoring (159 GPS collars on feedground elk). Female elk that are on native winter range (n=35) were captured in 26-28 January 2010 and fitted with GPS collars that will record location data every hour for two years. To quantify the difference in body condition between fed and unfed elk, 20 fed and 19 non-fed elk were captured in mid-March 2011, and their percent body fat measured as an indicator of nutritional condition. Fed elk averaged 6.1% body fat and unfed elk averaged 4.9%; a difference that was marginally significant. To test for differences between groups in migratory behavior, we conducted time to event modeling for arrival on and departure from summer range, while accounting for time-dependent environmental variables (e.g. weather, NDVI, feedground operation). Fed elk arrive on summer range later and leave earlier, spending an average of 26 fewer days on summer range. In spring, fed elk are less responsive to NDVI and length of feedground operation (i.e. feed is put out for elk) strongly influences and delays their arrival to summer range. In autumn, fed elk are more responsive to weather events, departing summer range following decreasing temperature and increasing precipitation. In addition, our migration work identified critical migration corridors and evaluated elk fidelity to migration routes to aid in conservation. Summer home range size of fed elk was about half that of unfed elk. To evaluate summer habitat selection, we developed resource selection functions for individual elk and compared fed and unfed elk. Habitat selection was primarily similar, with unfed elk showing more significant selection for two habitat variables. To evaluate carry-over effects on foraging, during the summers of 2010 and 2011 fed and unfed radio collared elk were relocated and monitored on the ground to record foraging time budgets. Data analysis of observations revealed that both groups employ the same time budget strategy, dedicating most of their time to feeding and bedding behavior. We are also interested in whether any behavioral differences scale up to influence landscape distribution of elk, which we are evaluating using stable isotope analysis. Stable isotope values are influenced by diet and physiology, and disparities between fed and unfed elk should be reflected in distinct isotopic signatures in tissues such as fur, hoof, and tooth cementum.

Understanding the influence of body-condition on elk behavioral ecology throughout the year will provide insight into the generality of behavior-condition relationships and movement and distribution data that are crucial to effective conservation and management.

Initial stable isotope analysis from hair samples of elk during initial capture failed to show detectable differences with regards to isotope ratios. To determine if our hair location sampling was incorrect due to false assumptions regarding timing and rate of hair growth, we initiated a collaborative effort with Dr. Kreeger and his staff at the WGFD Sybille Wildlife Research Center to measure both hair and hoof growth rates using six captive elk. This portion of the project was initiated in December 2010 with the dyeing of a patch of hair on the elk’s back with Nyanzol D and filing a grooved notch into one digit 10 mm below the coronary corium. Measurements to record growth occurred monthly for one year and concluded on 29 December 2011. To our knowledge this has never been done on elk before. Initial analysis suggests there is no hair growth from December through April, rendering hair to isotopically distinguish elk unusable. Elk hoof growth rate averages 0.7 mm/month, resulting in 7-8 months of growth present on hooves which may be enough to distinguish fed from unfed elk harvested during the fall hunt season. We will use the growth rate knowledge to acurately determine the correct location on hooves to sample for growth that would have occurred while the elk was on a feedground in winter.

2010 fall elk hunter harvest sample collection was very successful with the collaboration of WGFD staff from the Jackson, Pinedale and Laramie regions. From the Pinedale and Jackson regions, samples were solicited from elk hunters at check stations in all hunt areas containing or adjacent to feedgrounds. Check stations in the Laramie region were prioritized based on what WGFD biologists felt would be good opportunities to sample elk that never feed on agricultural fields (this would help to serve as a base for unfed elk). Samples from 129 different elk were collected, including one hoof, one tooth and a pinch of hair. Elk hooves were sampled in 0.7 mm increments in summer 2012 and we are now awaiting laboratory analysis of both hooves and teeth.

Project Presentations

“Carryover effects of winter feeding on migration, habitat selection and foraging ecology of elk in western Wyoming” as a Masters’ defense seminar at the University of Wyoming. Laramie, WY. 25 July 2013.

“Influence of winter feeding on migration strategies of elk” at the Western States and Provinces Deer and Elk Workshop. Missoula, MT. 8 May 2013.

“Influence of winter supplemental feeding on summer foraging behavior of elk (Cervus elaphus) in west-central Wyoming” at the annual meeting of the Wyoming chapter of The Wildlife Society. Jackson, WY. 8 December 2011.

“Influence of winter supplemental feeding on summer foraging behavior of elk in western Wyoming” as a contributed poster in the Ecology and Habitat Relationships: Birds & Mammals session at the annual meeting of The Wildlife Society. Kona, HI. 8 November 2011.

“Influence of nutritional condition on migration, habitat selection and foraging ecology

of elk in western Wyoming” as a research in progress poster presentation at the annual

meeting of The Wildlife Society. Snowbird, UT. 5 October 2010.

Contact

Jennifer Jones

Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit

University of Wyoming, Dept 3166

1000 E. University Ave.

Laramie, WY 82071

307-766-5415 (office)

406-868-2637 (cell)

jjones60@uwyo.edu

Brandon Scurlock, Supervisor

Brucellosis-Feedground-Habitat Program

Wyoming Game and Fish Department

432 E. Mill St.

Pinedale, WY 82941

307-367-4353

Project Lead

Jenny Jones: She is currently pursing a Masters degree at the University of Wyoming investigating the influence of nutritional condition on elk ecology throughout their annual cycle. Other current interests include developing a stable isotope technique to differentiate between feedground and native winter range elk for landscape distribution. MORE »

Timeline

This project began in the fall of 2009 and concluded in August 2013. Initial capture and collaring of 35 elk on native winter range (unfed) was completed January 2010. Recaptures of 20 fed and 19 unfed elk were conducted in mid-March 2011 to measure percent body fat as an index of nutritional condition to quantify the assumed benefit to elk of attending feedgrounds. Two summer field seasons in 2010 and 2011 collected behavioral time budget observations on fed and unfed elk throughout the study area. GPS collars automatically dropped off and were retrieved in January 2012. Movement data, habitat selection and foraging time budgets were analyzed in 2012. Samples for stable isotope analysis were collected from WGFD hunter check stations during the fall 2010 elk hunt season and elk hair and hoof growth rates were calculated using six captive elk at Sybille Wildlife Research Center in coordination with Dr. Terry Kreeger and staff. Stable isotope analysis of elk teeth from captures and teeth and hooves from hunter check stations is still awaiting laboratory analysis to determine if fed elk can be isotopically distinguished from unfed elk. This project is largely complete as thesis defense occurred on 25 July 2013. Manuscript preparation is ongoing.

Funding & Partners

Greater Yellowstone Interagency Brucellosis Committee • Wyoming Game and Fish Department • Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation • Wyoming Governor’s Big Game License Coalition • Wyoming Chapter of The Wildlife Society • L. Floyd Clarke Greater Yellowstone Scholarship